By Robert "Bob" Bussey

There is a heated debate out there. One many poets like to avoid. One many don’t even like to recognize, and it’s not even political…. or maybe it is. It’s a debate that goes to the core of poetry, that goes to its past, its present and its future. It’s a debate that can best be framed as a question: Is Free Verse Poetry Garbage? Or Is Free Verse Just Prose Chopped into Shorter Lines?

Poetry was initially spoken or sung … the oral tradition. When Homer recited the Iliad or the Odyssey the phrases about the Greek heroes were sung or at least spoken. Hardly anyone could read back in those days. Eventually written text became popular.

At that time poetry had rules, it had structure, and that was pretty much across all cultures. When the English got ahold of the art form (yes, Poetry is an art form) they were concerned with the number and pattern of stressed syllables per line (Check out Shakespeare and his contemporaries) and that was coupled with a rhyme scheme.

Then something happened. In the 1900’s, or thereabout, free verse popped its head into the world. No meter, no rhyme, no syllable count, no iambic pentameter, no nothing. In fact there is little that separates free verse from prose. Prose: ordinary or plain everyday language used in speech or writing with no patterns or rhymes. I have heard many contemporary poets argue that structured poetry, poetry that actually has a rhyming pattern is ticky-tacky, it sounds silly, childish, forced. But that is the challenge: How do you make a structured poem, one with rhyme, etc. still have impact, still impart emotion, still make the reader see something in a new light. Form forces the poet to think, to edit, to test, to see if what is being set down or spoken has any impact.

Some might respond by arguing that poetry does not always have to rhyme, and that is correct. There are various forms of traditional poetry that do not rhyme but have some sort of syllable structure. A few examples:

Cinquain is a short, usually unrhymed poem consisting of twenty-two syllables distributed as 2, 4, 6, 8, 2, in five lines. Like this:

angels

kind beyond words

they protect and forgive

and make feelings of blissfulness

cherubim

Or, Haiku (also called nature or seasonal haiku) is an unrhymed Japanese verse consisting of three unrhymed lines of five, seven, and five syllables (5, 7, 5) or 17 syllables in all.

Pink cherry blossoms

Cast shimmering reflections

On seas of Japan

Copyright © Andrea

Or, shape poetry. Shape is one of the main things that separate prose and poetry. Poetry can take on many formats, but one of the most inventive forms is for the poem to take on the shape of its subject.

Birth of a Triangle

mama and papa and baby make three,

reaching sides of a three-sided tree.

oedipal winds rustle from leaves;

triangular shapes converting

dissimilarity into peeves.

straight lines connect

the corners turned;

mirrored sight

un-burned;

buried

am

i

Copyright © 2001 Alex Goldenberg

There are other examples, but they all differ from Free Verse in that they have some structure, or some syllable count, or some rhyming pattern. Free verse has no meter, no rhyme, no syllable count, no iambic pentameter, no nothing.

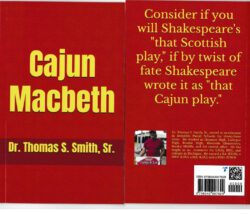

And now we come to Thomas Smith, who this article is all about. Thomas Smith is “old school” for the most part. His poems have structure, they have meter, they rhyme. He is in good company, since he follows in the footsteps of so many of the poets who wrote before free verse became so popular. C.S. Lewis may have said it best: “if you must read only old or new, read old, since it has stood the test of time.” (Not sure those were his exact words.) I’m not going to go into his background in any depth. But, Thomas has many letters behind his name (PhD, MA, M.Ed., BA, etc.) He is also published on many levels.

Let’s look at his poetry. The first one is a Quatrain. A poem with stanzas containing four lines, and with some rhyming pattern. In this case, he uses the AABB rhyming pattern. The syllable count can vary from line to line.

Street Preacher

I listened as I walked.

I heard him as he talked.

I saw him draw a crowd.

I heard him very loud.

He, to make his point, screamed.

He asked if we had dreamed.

He spoke, “Believe in Christ!”

He spat, “Evil enticed!”

They mostly kept walking.

They really were balking.

They think he is surreal.

They ignore his loud appeal.

We are the same I thought.

We paid attention naught.

We did not heed this man.

We do not need His plan.

They pass, turning each head.

They look away instead.

They, too busy to stop.

They think, “Where is the cop?”

He, a wilderness voice.

He says we have a choice.

He calls out, “Salvation!”

He quotes Revelation.

I, taken back, did halt.

I judge, “It’s not my fault?!”

I think his speech purloins.

I did throw him some coins.

He also uses a poetic form in this seven-stanza poem that is used to create emphasis or a strong sonic (verbal) effect. It’s called anaphora. You can find it used in spoken word poetry quite often. It helps drive home the poem’s message. So, who was the street preacher? Old time, new times, past, present? Perhaps a bit of all of that? Can you see and hear the Street Preacher? If you can, then the poem hits home.

The next poem uses a shape to help with the meaning or impact of the poem. But it also has a rhyming pattern (AAAA; BBBB; CCCC) The syllable count varies to help bring out the shape.

Antiquarian Angst

“Ozymandias,” the lesson’s focus

Change, the central locus

Teacher wish for hocus pocus

Student attitude quite atrocious

Teacher wrinkled lip with frown

No more on a pedestal looking ‘round

A shattered visage, feeling down

Gone is the old learning ground

Students with electronics in hand

Chrome book and tablet and AI mock where I stand

On the boundless and level intellectual sand

I am the “traveller” from the antique land.

Ozymandias refers to a poem by Percy B. Shelley, and the poem picks up a line, word, or phrase from that poem. Do you see the pedestal?

Ozymandias

I met a traveller from an antique land,

Who said—“Two vast and trunkless legs of stone

Stand in the desert. . . . Near them, on the sand,

Half sunk a shattered visage lies, whose frown,

And wrinkled lip, and sneer of cold command,

Tell that its sculptor well those passions read

Which yet survive, stamped on these lifeless things,

The hand that mocked them, and the heart that fed;

And on the pedestal, these words appear:

My name is Ozymandias, King of Kings;

Look on my Works, ye Mighty, and despair!"

Nothing beside remains. Round the decay

Of that colossal Wreck, boundless and bare

The lone and level sands stretch far away.

By Percy Bysshe Shelley

So, here are some quotes from the interview:

“Some people are brave enough to put their wondering down in words.”

“To me a lot of current poetry is doggerel, rough, crudely written verse.” (Doggerel is crude, poorly constructed or irregularly fashioned verse.)

“If I can write a Shakespearean sonnet with three quatrains and a couplet, that takes a little more skill than just vomiting words on a page, or expressing grief, or whatever it is.”

“When you can express yourself and still have some poetic form in your poem, to me that makes it better.”

“If you are using metrical feet, then finding the words that fit takes more skill.”

A metrical foot refers to the combination of stressed and unstressed syllables in a line of poetry. When these feet are combined, they sometimes create a pattern. These patterns help to create rhythm in poems.

Metrically organized poems were more common in the 17th, 18th, and 19th centuries. They’ve fallen out of favor with modern and contemporary poets due to the restrictive qualities and traditional implications of the poems. When creating a poem with meter, a writer has to ensure that certain words have a certain number of syllables, not to mention whether or not they’re stressed. This creates restrictions that most contemporary poets are uninterested in dealing with. The same can be said for rhyme schemes. When a poem uses neither a structured meter or rhyme it is written in free verse.

Here is a sonnet written by Thomas that has structure, rhyme, and metrical feet.

Blue-Eyed Fire

The child with hair of red and face so fair

A smile so sweet with radiance so bright

And temper’ment like whirlwind of ill air

When worldly ways with hers collide with fright.

This girl of beauty, she of Irish blood

She who has me around her finger wrapped

With tears of crystal drops her face to flood

And thus has me and my emotion trapped.

Her temper hot as flame of blue-eyed fire

While she is seeking her wish—her own way

The eyes of blue as masks of her still ire

As I who said for her to end the play

Once more have had the final say—so said—

Over the child, a youth with hair of red

{This poem appeared in

Frost in Spring (1989) and in ArtBeat (1986).}

Poems can have structure, rhyme, have other poetic forms and be funny or humorous. Here is one that Thomas wrote and that was inspired by a story starter by Jim Smilie in the Alexandria Daily Town Talk. He told me that the idea started as prose, but then he took the prose and turned it into a poem. Not just by chopping up the sentences in the prose, as so many free verse poems do today, but creating new lines with poetic value.

The Great Orthodontic Train Robbery

Rich and renowned Boston dentist Percival Fauntleroy

Had in his mind that he looked a mere premolar boy

“A man I must be. I have to prove it to me.”

Was what he said over and over just to see

If his body would answer his dry mouth’s plea.

The advice of “Go West, young man!” he would heed

An opportunity to prove denticulation manhood he would need.

Fauntleroy closed his dental office all the while to proclaim

That dentigerous manhood he was really going to claim

With that implant in mind he boarded a San Francisco-bound train.

Somewhere in the Wild West the chugging train did lurch and jerk

To a stop to be boarded by robbers, each with halitosis and a smirk.

The leader of the Grinder Gang lowered his bandanna for all to see

But particularly and especially for the lovely and voluptuous ladies three.

He swaggered and announced with a bucktooth grin his name was C. C.

All eyes centered on C. C. with his fiery red beard and headful of unruly bright red hair.

C. C. smiled, winked, made goo-goo eyes, gave come-hither looks, all with a coquettish flare.

The leader of the gang, while the others leveled guns, flirted with the lovely women in dresses

By walking about, smiling to flash a gold crown, and gently tugging bountiful tresses.

Women flirted back, as Fauntleroy pondered the tough, manly qualities the robber possesses.

As C. C. moved about to each of the ladies and caressed each face and on each a kiss he placed,

His fellow robbers, taking watches, rings, currency, coins, necklaces—all the while they raced.

The gang with their new-stolen riches quickly took their loot and disembarked from the train,

But, of course, C. C. made a toothy grand exit from the ladies that was anything but plain.

Fauntleroy, sitting there grinding his teeth, wondered and pondered with his manly brain.

The boyish Boston dentist departed the train at the next station to achieve his manly goal.

He knew he must create a new Western legend whose amalgam deeds were yet untold.

He assembled his own jawsmith gang to be led by himself with a new legendary name

The Doc Plaque Gang would enter, compete, and win the train fame name game.

The art of train robbery would bridge new heights and would never be the same.

“Bicuspid!” exclaimed dentist Percival Fauntleroy, the soon-to-be dental train robber.

“When old train robber gangs learn of our exploits, all they will be able to do is slobber!”

Doc Plaque devised a brilliant train robbery plan that would certainly pulp fiction ensure

That the Doc Plaque Gang, filling all of its legend’s expectations, would definitely endure.

That Doc Plaque would become known as a manly man. “Bicuspid! It was for sure!”

The gang Doc Plaque pulled together were not yet men of fame or even honorable mention.

They were Gene Ist, Oral Robbins, Pio Rhea, and, of course, the Doc of that boyish detention.

Drifter Gene Ist, constantly toking on roll-your-own tumble weed cigarettes, was always high.

Oral Robbins, an out-of-luck, snaggle-toothed street preacher, was another one that drew nigh.

Pio Rhea, unemployed Mexican chef and Tequila brew meister, joined with an enameled sigh.

Even though he always took a toke, high Gene Ist was the Doc’s right-hand nitrous oxide man,

And so Doc Plaque and Gene Ist did develop a great manly and legendary train robbery plan.

Doc, along with his right-hand man, explained the robbery plan and its orthodontia rationale.

The planners looked at the other dreamers and promised money for each and every Doc pal.

They would pull the job as the train slowed to cross the decaying bridge over the Root Canal.

The gang desired currency and jewelry and coins; those items were all on the collective brain.

Said Oral, “I would give all my wisdom teeth if them crown jewels was on that thar train.”

But for Doc Plaque saying the money was the crowning glory was just a paltry fabrication.

Because for the Doc, money was just an aside, and this first criminal act sets the foundation,

And the actual event with the ladies swooning would proclaim loudly his manhood declaration.

The old decaying Root Canal bridge design reminded Doc of his latest orthodontic training.

Doc thought the bridgework design a very good sign, and the gang showed no complaining.

Doc visualized the passenger and robber interaction that would yield desired manly abstraction.

But he knew that once the criminal infraction gained necessary traction to cause counteraction,

It would produce for him redaction of his boyish exaction and growth of his manly satisfaction.

The chugging train approached the orthodontic-structured bridge. As if on cue, it did slow.

Three of the gang were nervous, but not the Doc. The gang leader shouted, “Bicuspid, go!”

Before the turn as the train went slow, the gang spurred its horses and to the train drew nigh.

Pio and Oral galloped ahead to the locomotive and ordered the engineer to stop with a loud cry.

Doc and Gene moved to the passenger car, jumped on at opposite ends, and yelled to the sky.

Bursting through the doors in an instant, Doc, instead of pulling molars, pulled his gun.

Gene menacingly waved his double-barrel around; all passengers raised hands in unison.

An older male passenger, clutching his travel satchel, begged the outlaw gang not to shoot.

Doc bravely and quickly responded, “Open your mouth again, and I’ll drill ya, ya old coot!”

Gene blasted the roof with a single barrel and then puffed away at his tumbleweed cheroot.

In his weed-clouded mind, Gene was now the legendary “high” plains drifter of dime novels.

Pio and Oral in the locomotive felt power in guns and would never again be one who grovels.

But the transformation of a boyish man to a manly man was taking place in Doc the legendary.

Because he had not shaved in weeks, his face had become quite hairy and really sort of scary.

Percival was a different carie-free man; he was the beneficiary of his own heroic commentary.

The passenger car was his stage, and he was the acclaimed Shakespearean actor of renown.

The passengers were his captive audience; each woman an adorer; each man a mere clown.

All eyes and all ears were on the main performer, the enamel star—the one, the only Doc Plaque.

Doc, his manhood now alive and intact, decided that with the beautiful women he would interact.

He pranced up and down the aisle and winked and smiled and all kinds of flirtation did transact.

When Doc Plaque brandished his Colt .45 all around, the men thought he could not be disarmed.

All of the women—beautiful and not so—were mesmerized by Doc, not accidentally, charmed.

What the men did not know was that each cartridge chamber of the Colt .45 was only a cavity

Because Doc Plaque in all his excitement for the train robbery with all of its intense gravity,

Had forgotten to load the Colt .45 before beginning his ascent into his manhood of depravity.

He twirled to shout to the amalgam of men passengers, and with firm-set jaw he yelled out:

“You thumb sucker! You human abscess! You dry socket! You canker sore! You sauerkraut!”

The good doctor now dutifully again turned his attention and charm to the women in a rush.

The beautiful ladies blushed at Doc’s manly antics, and sexy Flossy in a swoon did gush,

“If only he would bathe, brush his teeth, and get decent clothes . . . ” Now Doc said, “Hush!”

“Pardon me, ladies,” Doc said to all the women passengers, “but I have an inlay job to do here.”

So Doc in a manly amble and with a Don Juan outlook advanced in this passenger car to its rear.

Now Doc Plaque with the confidence of the legendary lover produced a flirtation comprehensive.

Doc kissed lips, held hands, touched cheeks, waxed romantic but did not purloin to be offensive.

For unlike an impacted tooth, this train robbery for the passengers proved quite inexpensive.

Bicuspid! Doc had not forgotten to clean them out, for that procedure was not his prime intent.

Remember that his goal was to capture his manhood and prove it to all with legendary content.

He wanted all the passengers to leave the train at the next station with the legend of Doc Plaque.

He knew his gang in its giddy state would notice lack of loot at the hideout when they got back.

Doc, a rich man, previously placed bags of his money and dental fringe benefits there in a stack.

Doc signaled his gang to release its control on the train, now completed his robbery reputation.

“This is Doc Plaque Gang territory, and all other train robbers keep out!” was his declaration.

All this was the manly stuff that Western legends are made of, at least in Doc’s human brain.

The fear and loathing of the Tartar of the West, no longer the boy dentist, would forever remain.

Doc, now transcendental and with newly receding gums, extracted himself nicely from the train.

He does write some of his poems in free verse, so we will end this with one of

those. This is one from an experience that he had at the US border.

Star-Spangled Eyes

I, with my family, stood on the international bridge

over the Rio Grande,

Looking into Mexico.

Below me, on the near bank was another

man with his family,

Looking into the United States.

Through a hole in the fence, he carefully handed his

small child to his wife.

“Illegal aliens,” I told my family as I pointed, “coming to

America.”

That sight is forever burned into my memory.

It haunts.

What I took for granted, he pursues.

That father had star-spangled eyes, and he gave

me back mine.

(“Star-Spangled Eyes” was first published in the Spring 2001 issue of

Trends and Issues: The Quarterly Publication of

the Florida Council for the Social Studies.)

Robert Bussey is a local attorney and poet who has resided in CenLa since 1986. He interviews other poets and then writes these articles to help promote poetry. You can reach him at Rlbussey450@icloud.com if you are a poet and would like to be interviewed.