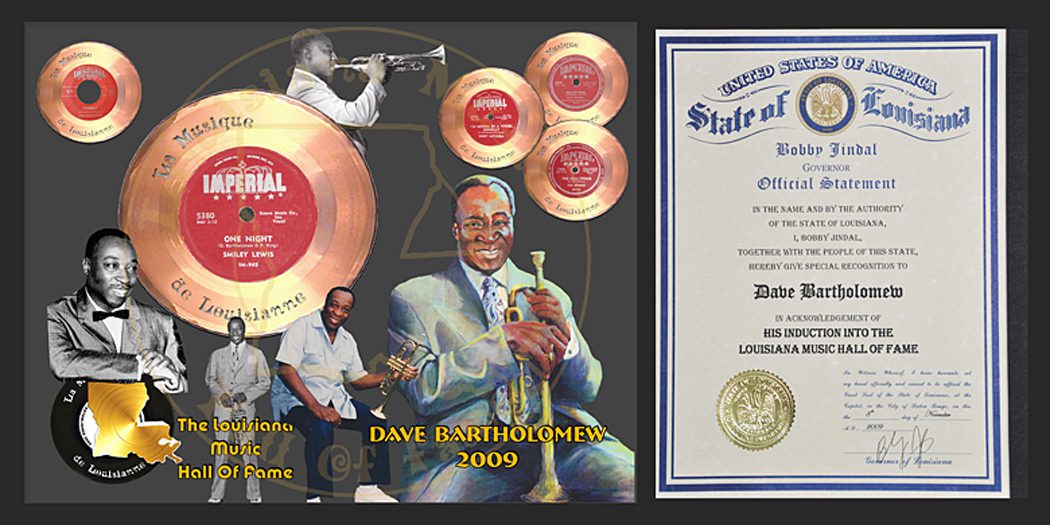

from Louisiana Music Hall of Fame

Dave Bartholomew (Dec. 24, 1918-June 23, 2019) was a catalyst in molding and shaping the New Orleans sound during rock & roll’s formative years. His contributions were officially acknowledged in 1991 when he was inducted into the Rock & Roll Hall of Fame. Through his association with Cosimo Matassa, he helped develop Smiley Lewis, Lloyd Price, Huey “Piano” Smith, Chris Kenner, Robert Parker, Frankie Ford, James Booker, James “Sugar Boy” Crawford, Roy Brown, Chris Kenner, and Earl King. The biggest name with whom Bartholomew will be eternally linked, however, is Fats Domino. The two collaborated to co-write more than seventy of Domino’s hit songs. They produced hundreds of millions of dollars in record sales, earning them a spot in the Guinness Book of World Records.

Born in Edgard, Louisiana, in St. John Parish, his family moved to New Orleans while he was a youngster, and he was fortunate enough to learn trumpet and more from Louis Armstrong’s teacher, Peter Davis. Following World War II, Bartholomew returned home and put together his own band which soon became one of the most popular in New Orleans. The band was comprised of Bartholomew, saxophonists Lee Allen and Red Tyler, and drummer Earl Palmer.

In 1949, Bartholomew and his band were performing in Houston when he met Lew Chudd, owner of Imperial Records. Chudd at the time was selling MExican music and was in Houston to scout for talent, but was also interested in marketing rhythm and blues. He hired BArtholomew’s band to play sessions at J&M Studio in New Orleans. In 1949, Chudd was in New Orleans to help to set up the first session. He and Bartholomew went to the Hideaway Club on a Friday night, where Chudd heard Fats Domino for the first time. Fats was brought into J&M Studio, and the Bartholomew-Domino partnership with Imperial Recordsand Lew Chudd was born. Their first recording session was held and eight songs were recorded. One of those songs was The Fat Man.

Fats was Imperial’s biggest seller throughout the 1950’s (second overall only to Elvis), thanks in large part to Bartholomew’s arrangement and production genius. The years 1956 and 1957 were the most productive for Fats and Bartholomew with the pair placing seventeen songs on Billboard’s Hot 100. Three of those, I’m Walkin’, Blue Monday and Blueberry Hill cracked the Top Ten.

Bartholomew didn’t like Blueberry Hill. Fats did, but it nevertheless took the better part of a day to get it on tape and Bartholomew felt it still didn’t sound right, probably because there was never a single take that was acceptable. The song had been a headache for everyone in the recording studio, including Domino and Bartholomew, because Fats couldn’t remember the words, and there was no sheet music. Several takes of the song were finally spliced together to get a usable copy, a real innovation in those early days of post-production, but Bartholomew was still dissatisfied with the song. He even tried to prevail on Chudd to not release the song. Chudd released it anyway because he didn’t have anything else from Fats. Bartholomew protested, saying the song was no good. Two weeks after its release, Chudd called Bartholomew and told him Blueberry Hill had just surpassed three million copies sold.

His songs were also popularized by Gale Storm (I Hear You Knocking), Elvis Presley (One Night and Witchcraft), Pat Boone (Ain’t That A Shame), and Ricky Nelson (I’m Walkin’). As his career moved into the ‘70s, he worked with Elton John, The Rolling Stones, Paul McCartney, Hank Williams, Jr., Bob Seger, Cheap Trick, Elvis Costello, and Joe Cocker. His songs have also cropped up in movies like The Blues Brothers, American Graffiti, and The Girl Can’t Help It.

It became difficult for Bartholomew to turn on the radio and not hear several songs that he’d produced. The success of Fats and Bartholomew continued through the decade of the 50’s, with Fats scoring his last Top Ten hit with Walkin to New Orleans. Even after the gravy days initially ran their course, Bartholomew still received offers from New York and the West Coast. He chose to remain in New Orleans, however.