by Doug Ireland

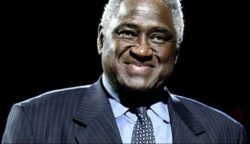

Willis Reed died last week, 80 good years behind him, his big heart and 6-foot-9 frame worn out from a life well lived.

He was enshrined in the Louisiana Sports Hall of Fame in 1982, eight years after bad knees ended his basketball playing days carrying him from country kid to the front of a Wheaties cereal box. One of those, along with a New York Knicks warmup jersey, are on display at the LSHOF museum in Natchitoches. He’s also celebrated at the Naismith Basketball Hall of Fame, where the world’s best are showcased.

Although basketball became his pathway to prominence, when he retired from a lengthy career as a coach and in NBA front offices, he and his second wife Gail came home to the rolling, pine-shaded hills in north Louisiana. Nearly 20 years later, on March 21 he drew his last breath at the North Louisiana Medical Center in Ruston, a few miles away from his home.

Born on his grandfather’s farm near Hico, in the countryside near Dubach, he was raised around Bernice, and enjoyed fishing and hunting – something iconic north Louisiana outdoors writer Glynn Harris noted continued throughout his life.

“Really miss him,” wrote Harris last week. “He was one of my very favorites to interview and feature in an article.”

Reed talked to Harris about hunting squirrels and raccoons with his dad, Willis Sr., as a kid, and his resulting love of the outdoors – owning a hunting lease in Pennsylvania while he starred in the NBA, then after hanging up his sneakers, taking trophies like whitetail deer, mule deer, cougar, caribou, antelope, elk and more for his walls, while fishing for bream with his grandkids. He treasured memories of fishing with his dad.

By eighth grade he was already over six feet tall, and he kept growing. Reed became the center of a championship West Side High School basketball team in Bernice, a star on the state championship football team, and threw the shot put and discus for the track team.

Little known but true: he was first recruited by coach Eddie Robinson to play football at Grambling. But Reed wisely decided basketball was his future, donning No. 51 for coach Fred Hobdy’s Tigers.

In his sophomore season, he was the driving force on a Grambling team that won the NAIA national championship – the same title that LSUA’s basketball team narrowly missed, on a 3-point buzzer beater, in 2017.

After his senior season, Reed was chosen to play for the United States in the 1963 Pan American Games for countries in north and south America, and led America to a gold medal. He was drafted in the NBA by the Knicks, and in an amazing 10-year career became one of the game’s all-time greats.

He kept coming home. Ted Lewis, a Louisiana Sports Hall of Fame sportswriter, remembers an unexpected encounter with Reed.

“In 1974 – my first year in Monroe – I’m covering a Carroll-Richwood game at Richwood.

“Richwood had one of those gyms with a stage taking up one side and only room for a few rows of seats on the other side, maybe 3-4 as I recall. I was at the scorer’s table which was on the stage. To say the obvious, the place was packed.

“Herschel West, who had been a great player at Grambling, was the Richwood coach. It’s late in the game and Herschel calls time out – not to coach his team, though.

“At the entrance to the gym was Willis Reed, who was injured during his final season and was on crutches, and his old friend had noticed. Herschel, who had been on Grambling’s NAIA championship team with Willis, called time out so the crowd could recognize him,” recalled Lewis. “It was quite a moment.”

Reed was the centerpiece of another moment that lives forever in hoop history, on its biggest stage, Madison Square Garden. It was Game 7 of the 1970 NBA Finals, Knicks vs. the Los Angeles Lakers, led by all-time greats Wilt Chamberlain, Elgin Baylor and Jerry West. Reed was New York’s team captain, soon to collect the NBA MVP award, but he was badly hurt. He had torn a thigh muscle in Game 5 and sat out Game 6. His status for the decisive game was doubtful, at best.

Reed was not on the court while Knicks and Lakers were minutes away from tipoff, warming up, with everyone and everything hinging on the question: would Willis play tonight? An immense roar erupted from the 20,000 in the stands as he strode out onto the court and took a few warmup shots.

“We were all out warming up, and we know that he was probably gonna take a shot,” teammate Bill Bradley told the New York Post. “Although quite frankly, I didn’t know he was gonna take a shot. But [Dave] DeBusschere said he knew.

“And when he came out, it was like electricity coursed through the whole arena. I remember Baylor, West and Chamberlain stopped warming up and watched him. I figured at that moment we were in pretty good shape.

“Then when (the game began) he hit his first two shots, that was amazing, that took it to another level. And then Walt Frazier had the best seventh game of any player in history, picking up on that inspiration.”

“He was the catalyst for us,” said Frazier, “because we were a team that was doubtful we could win without him. So, when we saw him, we perked up like, ‘We can do it.’ And I’ll never forget, I saw Wilt; I saw Baylor and West. When Willis came on the court, they stopped doing what they were doing. They were so concerned. And I said to myself, ‘Man, we got these guys.’ And then he would come out and make his first two shots. The rest was history from there on, and that was Willis Reed, man.”

The Knicks won, and Reed was voted the MVP of the NBA Finals. They were champs again in 1973, and Reed again was league MVP and Finals MVP.

“He was The Captain — that says it all,” Bradley said. “He was the backbone of the team. He was the guy that took us to the first championship by his courage, and by his unselfishness.”

“They don’t make them like that anymore. Kind guy, he’d loan you his car, loan you his money,” said Frazier. “He lived in Queens. I didn’t know his kids from the neighborhood kids. His house was like Grand Central Station. People were just in and out. That’s how the man is. He shares everything. He was quite a man.

“More than anything it was the personal things,” Frazier continued. “We know about his exploits as a player, but as a person he was even better.”

That’s quite an epitaph.